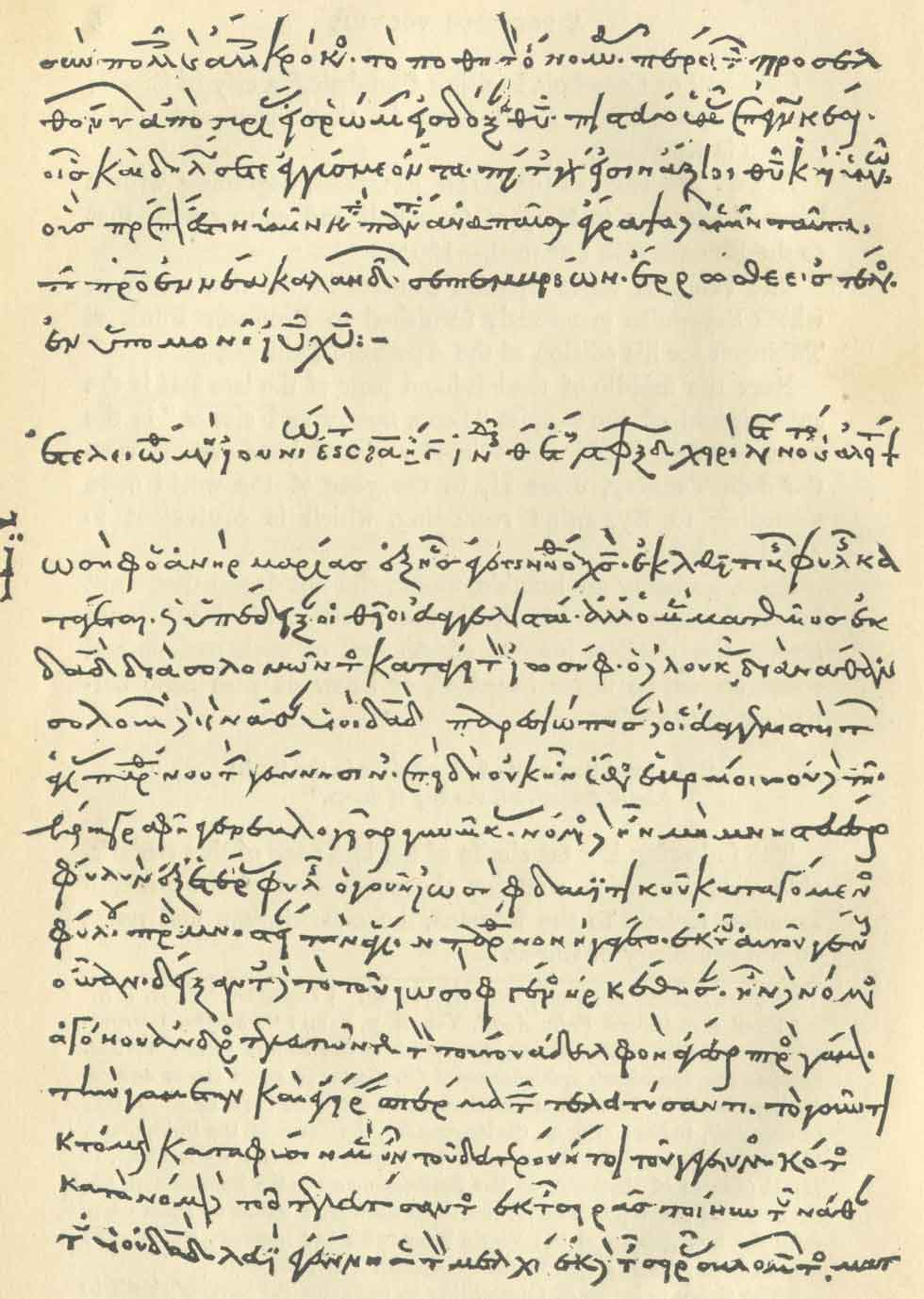

This is the final installment of this little followed series. Today we look at the Didache (Ignatius press' catechetical series might come to mind, it follows in the footsteps of the early Church catechetical document). The Didache is an interesting document that was rediscovered on one and half centuries ago. Previously there were only excerpts in the writings of the Church Fathers. It is was highly reverenced and considered as great source of early Christian life There are three Eucharistic chapters, nine, ten, and fourteen.

Chapter 9 can be seen as the offertory rite of the early church. If one were to compare chapter nine with the offertory rite in the Ordo Missae there are definite similarities. The Ordo Missae says “Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation, for through your goodness we have received the wine we offer you: fruit of the vine and work of human hands it will become our spiritual drink. Blessed be God forever.”[ii] The Didache says, “First concerning the Cup, ‘We give thanks to thee, our Father, for the Holy Vine of David thy child, which thou didst make know to us through Jesus thy child; to thee be glory forever.’”[iii] There occurs a thanksgiving for the gift of the wine given from the Father to be returned to him in offering. Then there is the acclamation, blessed be God forever and to thee be glory forever. There continues here the typological aspect of the Eucharist, which began in the gospel of John and in the Pauline letters. The Eucharist fulfills the wine that sits next to the showbread outside of the Holy Holies. Chapter nine continues with the Johannine typology of the manna. “As this broken bread was scattered upon the mountains, but was brought together and became one, so let thy Church be gathered together from the end of the earth into they kingdom, for thine is the glory and the power through Jesus Christ forever.”[iv] The final aspect of chapter nine and probably its defining Eucharistic aspect is the excluding of unbaptized from the meal. “But let none eat or drink of your Eucharist except those who have been baptized in the Lord’s name.”[v] The only reason to exclude unbaptized from a meal would be a sacramental meal wherein only those who were called into the flock can partake. This hints at a sacramental structure based on the primacy of baptism in the sacraments of initiation.

Chapter ten is said to a prototype preface. The same elements occur, thanksgiving for the gifts received and praise by way of the Sanctus, “Hosannah to the God of David. If any man be holy, let him come!”[vi] and “Holy, Holy, Holy Lord God of hosts. Heaven and earth are full of your glory. Hosanna in the highest. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.”[vii] These are remarkably similar. Rordorf says that the Sanctus originates from the Jewish meal blessing. Also, within chapter ten there is the manifestation of the eschatological nature of the Eucharistic sacrifice in the words Maran atha. “The expression of the expectation of the parousia which St. Paul has preserved for us, confirms what he himself has allowed us to see of the eschatological orientation of the first Christian Eucharists, where they ‘proclaimed’ the death of the Lord, ‘until he comes.’”[ix] Finally, chapter 10 demands the presider, or prophet as he is called, to chose the place and time for the celebration. The presider is said to be the bishop, who proclaims the word of God and officiates at the celebration.

Chapter fourteen deals with the Sabbath. It proscribes that the Eucharist should be celebrated “on the Lord’s Day.”[x] One should come clean from sin. This is the first discussion of fruitful reception of the Eucharist. “After confessing your transgression that your offering may be pure; but let none who has a quarrel with his fellow join in your meeting until they be reconciled, that your sacrifice be not defiled.”[xi] If one has the stain of sin his offering of himself at the Eucharistic sacrifice will not be pure. Furthermore, if you are distracted be a quarrel this quarrel will prevent you from receiving the sacrament, which is an offering of self to Christ, as best as possible. Herein also lie the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist. If one stained by sin or not properly recollected, one cannot sacrifice a proper spiritual sacrifice in union with the unbloody sacrifice on the altar. “For this is that which was spoken by the Lord, ‘In every place and time offer me a pure sacrifice, for I am a great king,’ saith the Lord, ‘and my name is wonderful among the heathen.’”[xii]

[i] Willy Rordorf, “The Didache,” in The Eucharist of the Early Christians, trans. Matthew J. O’Connell (NY: Pueblo Publishing Company, 1978), 10-11; Andre Garakas, The Origin and Development of the Holy Eucharist: East and West (NY: St. Paul’s, 2006), 69; O’Connor, 6; and Bouyer, 117-118.

[ii] PDF of New Translation into English, 2008 from

[iii] Didache in The Apostolic Fathers, vol. 1 of the Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998), 323

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] PDF of New Translation into English, 2008 from

[viii] Rordorf, 14.

[ix] Bouyer, 118-119.

[x] Didache, 331.

[xi] Ibid.

No comments:

Post a Comment