|

| St. Thomas More |

|

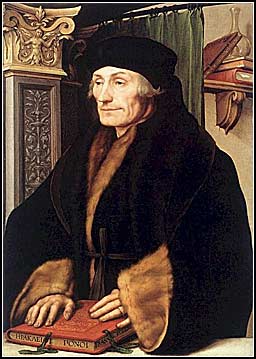

| Desiderius Erasmus |

The encounter was described by Eramus in 1523. It occurred in 1499 at the Greenwich house of Sir William Say, to whose daughter Mountjoy was betrothed and who was a family friend of the Mores. “Thomas More, who, while I was staying in the country house of Mountjoy, had paid me a visit, took me out for a walk for relaxation of mind to a neighboring village.”[xiv] The neighboring village was Eltham were there was a royal residence. Prince Henry (to be Henry VIII), then eight or nine years of age, was currently residing there. More, a school friend, Edward Arnold, and Erasmus paid a visit to the prince the former two offering verses for the younger son of the king.[xv] It can be deduced that two students of law and budding scholar would have had an intellectual discussion on their way to such a fare. Erasmus always enjoyed intellectual conversation, and More always sought advice from his scholar friends, St. John Fisher, Fr. John Colet, Thomas Linacre, Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, and William Lily. Their conversation, as mentioned before, was in Latin, for although Erasmus traveled all throughout Europe for most of his life he failed to learn any of the vernacular languages except for use in general affairs, something Reynolds continually points out. Nonetheless, this spurred a familial relationship between the two. Erasmus was said to always have a room at More’s house in London and the same would have been the case when he moved to Chelsea had Erasmus ever returned to England in the last ten years of More’s life. In the first of their correspondence, a letter from Erasmus to More, one can begin to understand their intimate relationship for Erasmus calls More “sweetest Thomas” and “dear More.”[xvi]

From this first meeting comes the first principle of friendship: a personal physical encounter. More and Erasmus met face to face. They even went on a small journey together. They walked and talked and shared mutual likes and dislikes (although probably more of an intellectual nature, than say food). This takes into account the hylomorphic nature of the human person. In meeting a true friend, one encounters them both body and soul. In that first letter, Erasmus wrote that he ‘grew sick’ for want of both More and his handwriting, i.e. his physical presence and the inner thoughts of his soul. In our present circumstances, many people meet online. Here they imagine true friendships have come about. Although they may have seen pictures of their friend, nothing, I mean nothing can take the place of a physical encounter with a person. Here there is a natural epistemology of the dignity of this person. Their existence although conceptual before, becomes actual in the intellect. Many friendships fail because they lack this initial physical encounter.

Erasmus left England after that most joyous sojourn only to return five years later. He would travel Europe, a vagabond scholar, moving from place to place never staying anywhere long enough to settle. It was only when his age and his health at the end of his life forced him to stay at Louvain or in Basel for extended periods of time. He was constantly writing letters. Moving from place to place, he kept correspondence with all those he met. They, including More, will respond. These seemed to be a normal affair because there is a great body of extant letters from both More and Erasmus. One of the general themes, when either mentions the other or writes to the other is mutual respect. This can be seen from Eramus in a letter he wrote while living and working with More on Latin translations of Lucian.

For I do not think, unless the vehemence of my love leads me astray, that Nature ever formed a mind more present, ready, sharpsighted and subtle, or in a word more absolutely furnished with every kind of faculty than his. Add to this a power of expression equal to his intellect, a singular cheerfulness of character and an abundance of wit, but only of the candid sort; and you miss nothing that should be found in a perfect advocate.[xvii]

It can also be seen in a letter from More to Martin Dorp. Dorp was a theologian at Louvain who took to arguing and slandering Erasmus for his writing of Praise of Folly (which is dedicated to More and in part inspired by him). More wrote to Dorp defending his friend.

I am definitely very much disturbed because, in your work, you give the impression of attacking Erasmus in a manner not all becoming to you or him. You treat him sometimes as if you despise him, sometimes as if you looked down upon him in derision, sometimes not as one giving him an admonition, but scolding him like a stern reprover or a harsh censor; and lastly, by twisting the meaning of his words, as if you were stirring up all the theologians and even the universities against him.[xviii]

Although to postmodern ears this sounds tame, it is both scathing criticism toward Dorp and a bold a defense for one of Erasmus’ most controversial works during his lifetime. They had each other in mutual respect. Both discussed the good in each other setting aside the bad for what was but rejoiced in the gift that God had given them. This is a lesson for contemporary friendships that seem to be based more on mutual use and than mutual respect. Although More was connected in England and Erasmus throughout Europe,[xix] neither used the other simply for personal advantage. One was always looking out for the mutual good of the other. When More entered the service of the king, Erasmus said something to the effect of, “I rejoice for the king that he has received so great a man, but I feel sorry for More for having to work for the king.” He truly cared for the well being of More. This job indeed would cost More his life.

Indeed, the crowning character of their friendship and probably the glue which kept such physically distant men so close together centered on their relationship with Jesus Christ, whom they met in Scripture and in Eucharist. One can, especially in More writing while in the tower of London, that he had a deep understanding of the Christian life and the Christian relationship with Jesus Christ. This is a prayer taken from his A Treatise on the Passion, “O my sweet savior Christ, who in your undeserved love towards mankind so kindly would suffer the painful death of the cross, suffer not me to be cold or lukewarm in love again towards you.”[xx] Erasmus because of the fame, sanctity, and martyrdom of his friend tends to be overshadowed in this area, especially since he was denounced by so many in the church. He detested the abuses and pure physicality of the popular piety of the veneration of relics. He wished to direct people towards the heavenly realities and the lives of the saints whose bones they venerate. He says this in his Enchiridion Militis Christiani, “Rise as by rungs until you scale the ladder of Jacob. As you draw nigh to the Lord, He will draw to unto you. If with all your might you strive to rise above the cloud and clamor of the senses He will descend from light inaccessible and that silence which passes understanding in which not only the tumult of the senses is still, but the images of all intelligible things keep silence.”[xxi] This indeed sounds like the advice of some of the Carmelite mystics that follow him and More later in the sixteenth century. Indeed, the light of Christ shined on this relationship. It strengthened it and sustained it. Beyond all intellectual and political pursuit that either were involved in, they were first men of God.

This seems to be the most lacking in contemporary friendships. As said before, they are centered not on mutual respect but on mutual use. They, following our current society, separate God from their relationships. He becomes the arbiter and blind watchmaker and the not the saving and all-loving ineffable one with whom all men desire the most true friendship. This is indeed the least talked about part of the friendship between Erasmus and More. This strengthens my claim of the problem for all of my secondary sources were written in the twentieth century. They cannot even see the true source and sustenance of their relationship. Reynolds see the basis as elusive be posits that their friendship was a harmony of spirit.[xxii] I would further that and say it is rather a harmony in and through the Holy Spirit. He both enlightens us and shows us the love of God.

Three principles of friendship, then, can be deduced from the relationship between Desiderius Erasmus and St. Thomas More. The first and most basic principle is a personal physical encounter. One must encounter the other person in their body face to face, if you will, just they did on that day as they walked to met Prince Henry. The second principle is mutual respect, without which the human qualities of the relationship will fail. One finds in the extant letters of More and Erasmus a constant building up of the other, each one always looking for the good of the other. The final and highest principle is a mutual relationship with and in Jesus Christ. A friendship with God begets true friendships with man.

[i] Ralph McInerny, “Lecture 7A -- Lesson Thirteen: Love: The Unity of Christian Life,” Notes from his course Introduction to St. Thomas Aquinas offered by the International Catholic University. www.icu.org

[ii] Richard Shoeck, “Telling More from Erasmus : An Essai in Renaissance Humanism,” Moreana. XXlII. 91-92 (Nov. 1986). 11-19.

[iv] Although it would be of great joy for me to follow their relationship from start to finish, and analyze each letter and work of theirs, such a work would be vastly outside the scope of such an essay. Consequently, I will focus specifically on those parts of their relationship wherein the principles of friendship can be drawn out.

[vi] Ackroyd, 20.

[x] Reynolds, 3. It is interesting that in a sense both More and Erasmus took up their father’s trades. More indeed became a lawyer of the highest order as Lord Chancellor of England. Erasmus became one of the foremost scholars of ancient languages who reprinted Church Fathers, the New Testament, and many adages of the Greek and Roman philosophers and orators. He, in a sense, became a master at the use of the printing press to disseminate his work. They both followed in the father’s footstep but only to surpassing them.

[xii] Ackroyd, 81.

[xiv] Reynolds, 22. (He quoted it without footnote or endnote, and I could not track down its source.)

[xv] It was the custom for scholars to offer verses on such occasions. Ackroyd, 83. Reyonolds, 22.

[xvi] Desiderius Erasmus, The Epistles of Erasmus: From His Earliest Letters to His Fifty-First Year, Volume 1, translated by Francis Morgan Nichols (NY: Russell & Russell, 1962), 212.

[xviii] St. Thomas More, Selected Letters, edited by Elizabeth Frances Rogers (New Haven: Yal University Press, 1961), 12.

[xix] He corresponded with popes and bishops throughout his lifetime. He was also a counselor to Charles V of Hapsburg notoriety.

[xx] A Thomas More Source Book, edited by Gerard B. Wegemer and Stephen W. Smith (Washington D.C: CUA Press, 2004), 266.

[xxi] Quoted in Bainton, 71.

No comments:

Post a Comment